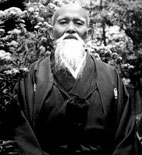

Aikido's founder, Morihei Ueshiba, was born in Japan on December 14, 1883. According to the founder's son, Kisshomaru, when Morihei was a boy, he saw local thugs beat up his father for political reasons. He set out to make himself strong so that he could take revenge. He devoted himself to hard physical conditioning and eventually to the practice of martial arts, receiving certificates of mastery in several styles of jujitsu. In spite of his impressive physical and martial capabilities, however, he felt very

dissatisfied. He began delving into religions in hopes of finding a deeper significance to life, all the while continuing to pursue his studies of budo, or the martial arts. By combining his martial training with his religious and political ideologies, he created the modern martial art of aikido. Ueshiba decided on the name "aikido" in 1942 (before that he called his martial art "aikibudo"and "aikinomichi"). On the technical side, aikido is rooted in several styles of jujitsu (from which modern judo is also derived), in particular daitoryu-(aiki)jujitsu, as well as sword and (possibly) spear fighting arts. Oversimplifying somewhat, we may say that aikido takes the joint locks and throws from jujitsu and combines them with the body movements of sword and spear fighting. However, it may be that many aikido techniques were the result of the founder's own innovation. On the religious side, Ueshiba was a devotee of one of Japan's so-called "new religions," Omotokyo. Omotokyo was (and is) part neo-Shintoism, and part socio-political idealism. One goal of Omotokyo has been the unification of all humanity in a single "heavenly kingdom on earth" where all religions would be united under the banner of Omotokyo. It is impossible sufficiently to understand many of O-sensei's writings and sayings without keeping the influence of Omotokyo firmly in mind. Despite what many people think or claim, there is no unified philosophy of aikido. What there is, instead, is a disorganized and only partially coherent collection of religious, ethical, and metaphysical beliefs which are only more or less shared by aikidoka, and which are either transmitted by word of mouth or found in scattered publications about aikido. Some examples: "Aikido is not a way to fight with or defeat enemies; it is a way to reconcile the world and make all human beings one family." "The essence of aikido is the cultivation of ki [a vital force, internal power, mental/spiritual energy]." "The secret of aikido is to become one with the universe." "Aikido is primarily a way to achieve physical and psychological self-mastery." "The body is the concrete unification of the physical and spiritual created by the universe." And so forth. At the core of almost all philosophical interpretations of aikido, however, we may identify at least two fundamental threads: (1) A commitment to peaceful resolution of conflict whenever possible. (2) A commitment to self-improvement through aikido training.

Although aikido is a relatively recent innovation within the world of martial arts, it is heir to a rich cultural and philosophical background. Aikido was created in Japan by Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1969). Before creating aikido, Ueshiba trained extensively in several varieties of jujitsu, and in swordsmanship. Ueshiba also immersed himself in religious studies and developed an ideology devoted to universal socio-political harmony. Incorporating these principles into his martial art, Ueshiba developed many aspects of aikido in concert with his philosophical and religious ideology. Aikido, as Ueshiba conceived it in his mature years, is not primarily a system of combat, but rather a means of self-cultivation and improvement. Aikido has no tournaments, competitions, contests, or "sparring." Instead, all aikido techniques are learned cooperatively at a pace commensurate with the abilities of each trainee. According to the founder, the goal of aikido is not the defeat of others, but the defeat of the negative characteristics which inhabit one's own mind and inhibit its functioning. At the same time, the potential of aikido as a means of self-defense should not be ignored. One reason for the prohibition of competition in aikido is that many aikido techniques would have to be excluded because of their potential to cause serious injury. By training cooperatively, even potentially lethal techniques can be practiced without substantial risk. It must be emphasized that there are no shortcuts to proficiency in aikido (or in anything else, for that matter). Consequently, attaining proficiency in aikido is simply a matter of sustained and dedicated training. No one becomes an expert in just a few months or years.

It is common for people to ask about the practice of bowing in aikido. In particular, many people are concerned that bowing may have some religious significance. It does not. In Western culture, it is considered proper to shake hands when greeting someone for the first time, to say "please" when making a request, and to say "thank you" to express gratitude. In Japanese culture, bowing (at least partly) may fulfill all these functions. Bear in mind, too, that in European society only a few hundred years ago a courtly bow was a conventional form of greeting. Incorporating this particular aspect of Japanese culture into our aikido practice serves several purposes: It inculcates a familiarity with an important aspect of Japanese culture in aikido practitioners. This is especially important for anyone who may wish, at some time, to travel to Japan to practice aikido. There is also a case to be made for simply broadening one's cultural horizons. Bowing may be an expression of respect. As such, it indicates an open-minded attitude and a willingness to learn from one's teachers and fellow students. Bowing to a partner may serve to remind you that your partner is a person - not a practice dummy. Always train within the limits of your partner's abilities. The initial bow, which signifies the beginning of formal practice, is much like a "ready, begin" uttered at the beginning of an examination. So long as class is in session, you should behave in accordance with certain standards of deportment. Aikido class should be somewhat like a world unto itself. While in this "world," your attention should be focused on the practice of aikido. Bowing out is like signaling a return to the "ordinary" world. When bowing either to the instructor at the beginning of practice or to one's partner at the beginning of a technique it is often considered proper to say "onegai shimasu" (lit. "I request a favor") and when bowing either to the instructor at the end of class or to one's partner at the end of a technique it is considered proper to say "domo arigato gozaimashita" ("thank you").

Proper observance of etiquette is as much a part of your training as is learning techniques. In many cases observing proper etiquette requires one to set aside one's pride or comfort. Nor should matters of etiquette be considered of importance only in the dojo. Standards of etiquette may vary somewhat from one dojo or organization to another, but the following guidelines are nearly universal. Please take matters of etiquette seriously. 1. When entering or leaving the dojo, it is proper to bow in the direction of O-sensei's picture, the kamiza, or the front of the dojo. You should also bow when entering or leaving the mat.

2. No shoes on the mat.

3. Be on time for class. Students should be lined up and seated in seiza approximately 3-5 minutes before the official start of class.

If you do happen to arrive late, sit quietly in seiza on the edge of the mat until the instructor grants permission to join practice.

4. If you should have to leave the mat or dojo for any reason during class, approach the instructor and ask permission.

5. Avoid sitting on the mat with your back to the picture of O-sensei. Also,

The concept of ki is one of the most difficult associated with the philosophy and practice of aikido. Since the word "aikido" means something like "the way of harmony with ki," it is hardly surprising that many aikidoka are interested in understanding just what ki is supposed to be. Etymologically, the word "ki" derives from the Chinese "chi." In Chinese philosophy, chi was a concept invoked to differentiate living from non-living things. But as Chinese philosophy developed, the concept of chi took on a wider range of meanings and interpretations. On some views, chi was held to be the most basic explanatory material principle - the metaphysical "stuff" out of which all things were made. The differences between things depended not on

some things having chi and others not, but rather on a principle (li, Japanese = ri) which determined how the chi was organized and functioned (the view here bears some similarity to the ancient Greek matter-form metaphysic). Modern aikidoka are less concerned with the historiography of the concept of ki than with the question of whether or not the term "ki" denotes anything real, and, if so, just what it does denote. There have been some attempts to demonstrate the objective existence of ki as a kind of "energy" or "stuff" that flows within the body (especially along certain channels, called "meridians"). So far, however, there are no reputable studies which conclusively demonstrate the existence of ki. Traditional Chinese medicine appeals to ki/chi as a theoretical entity, and some therapies based on this framework have been shown to produce more positive benefit than placebo, but it is entirely possible that the success of such therapies is better explained in ways other than supposing the truth of ki/chi theory. Many people claim that certain forms of exercise or concentration enable them to feel ki flowing through their bodies. Since such reports are subjective, they cannot constitute objective evidence for ki as a "stuff." Nor do anecdotal accounts of therapeutic effects of various ki practices constitute evidence for the objective existence of ki - anecdotal evidence does not have the same evidential status as evidence resulting from reputable double-blind experiments involving strict controls. Again, it may be that ki does exist as an objective phenomenon, but reliable evidence to support such a view is so far lacking. There are a number of aikidoka who claim to be able to demonstrate the (objective) existence of ki by performing various sorts of feats. One such feat, which is very popular, is the so-called "unbendable arm." In this exercise, one person,, extends her arm, while another person, , tries to bend the arm. First, makes a fist and tightens the muscles in her arm. is usually able to bend the arm. Next, relaxes her arm (but leaves it extended) and "extends ki" (since "extending ki" is not something most newcomers to aikido know precisely how to do, is often simply advised to think of her arm as a fire-hose gushing water, or some such similar metaphor). This time, finds it (far) more difficult to bend the arm. The conclusion is supposed to be that it is the force/activity of ki that accounts for the difference. However, there are alternative explanations expressible within the vocabulary or scope of physics (or, perhaps, psychology) that are fully capable of accounting for the phenomenon here (subtle changes in body positioning, for example). In addition, the fact that it is difficult to filter out the biases and expectations of the participants in such demonstrations makes it all the more questionable whether they provide reliable evidence for the objective existence of ki. Not all aikidoka believe that ki is a kind of "stuff" or "energy." For some aikidoka, ki is an expedient concept - a blanket-concept which covers intentions, momentum, will, and attention. If one eschews the view that ki is a stuff that can literally be extended, to extend ki is to adopt a physically and psychologically positive bearing. This maximizes the efficiency and adaptability of one's movement, resulting in stronger technique and a feeling of affirmation both of oneself and one's partner. Irrespective of whether one chooses to take a realist or an anti-realist stance with respect to the objective existence of ki, there can be little doubt that there is more to aikido than the mere physical manipulation of another person's body. Aikido requires a sensitivity to such diverse variables as timing, momentum, balance, the speed and power of an attack, and especially to the psychological state of one's partner (or of an attacker). In addition, to the extent that aikido is not a system for gaining physical control over others, but rather a vehicle for self-improvement (or even enlightenment (see satori)), there can be little doubt that cultivation of a positive physical and psychological bearing is an important part of aikido. Again, one may or may not wish to describe the cultivation of this positive bearing in terms of ki.The following are some of the founder's teachings concerning the essence of aikido: Aikido is a manifestation of a way to reorder the world of humanity as though everyone were of one family. Its purpose is to build a paradise right here on earth. Aikido is nothing but an expression of the spirit of Love for all living things. It is important not to be concerned with thoughts of victory and defeat. Rather, you should let the ki of your thoughts and feelings blend with the Universal. Aikido is not an art to fight with enemies and defeat them. It is a way to lead all human beings to live in harmony with each other as though everyone were one family. The secret of aikido is to make yourself become one with the universe and to go along with its natural movements. One who has attained this secret holds the universe in him/herself and can say, "I am the universe." If anyone tries to fight me, it means that s/he is going to break harmony with the universe, because I am the universe. At the instant when s/he conceives the desire to fight with me, s/he is defeated. Nonresistance is one of the principles of aikido. Because there is no resistance, you have won before even starting. People whose minds are evil or who enjoy fighting are defeated without a fight. The secret of aikido is to cultivate a spirit of loving protection for all things. I do not think badly of others when they treat me unkindly. Rather, I feel gratitude towards them for giving me the opportunity to train myself to handle adversity. You should realize what the universe is and what you are yourself. To know yourself is to know the universe.